Interview with Verlin Darrow - The RV Book Fair 2025

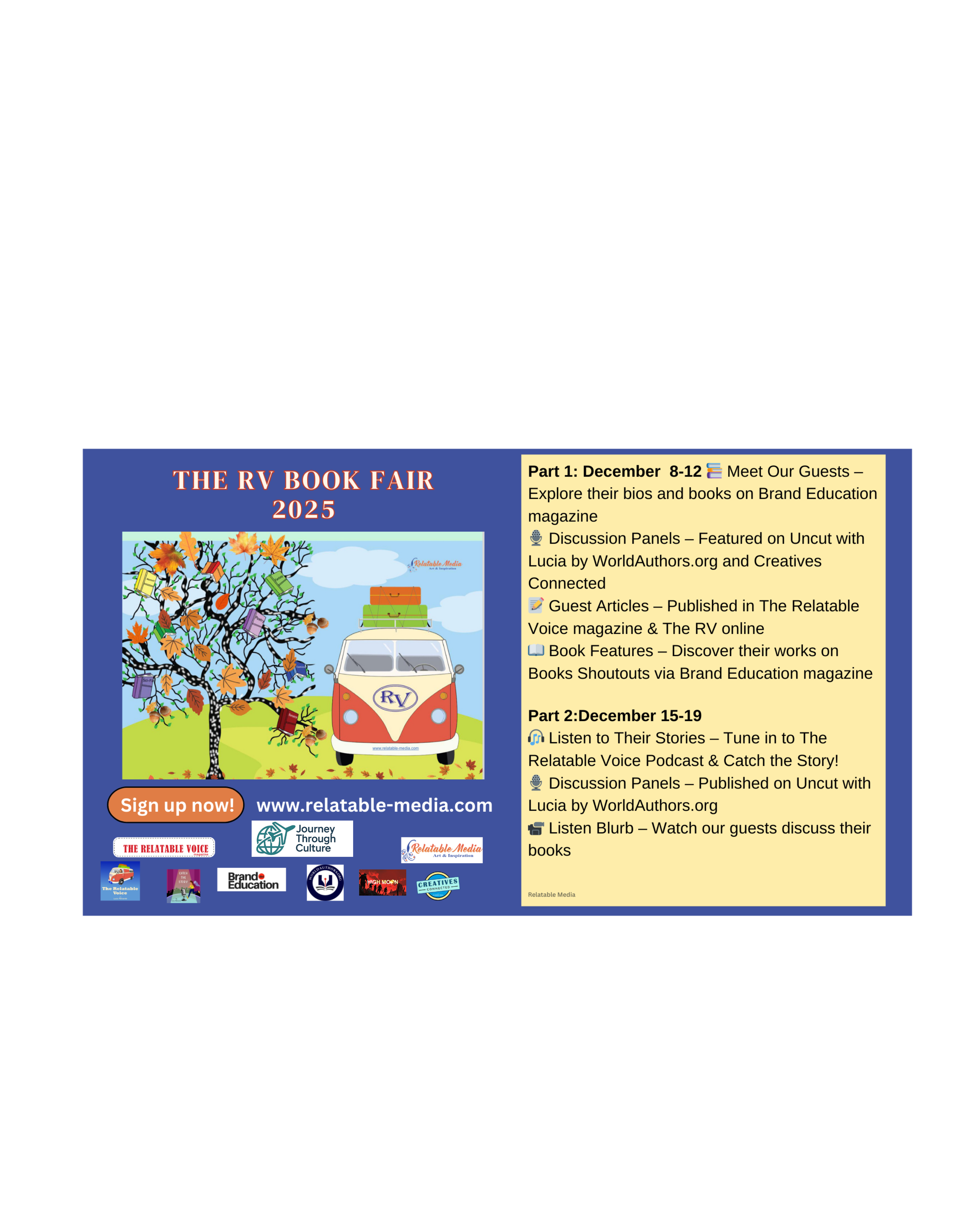

- The RV Book Fair 2025

- Dec 19, 2025

- 6 min read

Hello Verlin, what personal experiences most strongly influenced your writing?

The most significant influence on my writing came from a sudden and profound personal transformation I experienced at thirty-two—far enough in the rearview mirror now to have some perspective on it.

I’d been deeply depressed since childhood. At ten, with an odd and misplaced sense of willpower, I essentially divorced myself from my family and rejected most mainstream expectations about school and life. Cutting myself off from guidance and formative experiences was, in hindsight, a terrible idea. I retreated into my head and avoided direct experience altogether, afraid it might force me to change.

Even after years of therapy, things worsened to the point where I could barely function. I was starving myself of life itself—of experiences with weight or meaning. When my wife told me she would leave if I couldn’t find a way to change, something finally shifted. Over the next two weeks, reality broke through.

Colors became brighter and more dimensional. People felt real instead of like flat characters in a film. I realized I’d been living with highly filtered versions of reality. When those filters dropped, the intensity was terrifying. It felt like going from a one to an eight on a scale of experience. What I later realized was probably a normal level of perception felt overwhelming by contrast.

But I also felt alive. Even fear was better than the numbness I’d known before.

The most unexpected outcome—and the one that most affects my writing—was the realization that life contains far more than what appears on the surface. Raised as an atheist with no spiritual background, I became an obsessive seeker, traveling widely on a spiritual quest and eventually co-founding a small, benign spiritual community.

Because of this, I see my characters as capable of radical change. My work is infused with what passes for wisdom in my universe, and both my characters and I tend to experience life as absurd—or at least deeply unlikely.

Why did you gravitate toward thrillers and mysteries as your primary genres?

Early on, I discovered that plot and dialogue were my strongest skills as a writer. Most other elements of novel writing were difficult for me—and not much fun. So, I asked myself which genres played to my strengths and allowed me to sidestep what I found most challenging.

Thrillers and mysteries were the obvious answer. I’ve always loved reading them. The plots tend to fall out of me naturally, protagonists often have partners or sidekicks for banter, and—like my readers—I’m genuinely anxious to find out how the story resolves. I do almost no planning.

As for my antiheroes and villains, they draw heavily from my years as a psychotherapist. I’ve worked with people in a wide range of settings who embodied the traits I write about. That exposure has made it easier for me to get inside the heads of characters like Kinney in Kinney’s Quarry, who describes himself as a “benign psychopath”—someone trying to use a questionable skill set for as much good as possible.

I’ve known Kinneys. And worse.

What other activities keep you grounded outside of writing?

I play golf. It definitely keeps me grounded—though it’s rarely inspiring. Golf is brutally hard to master. A round of golf is basically signing up to be humbled, with the occasional fleeting moment of excellence. A writer once called it “a good walk ruined,” which feels accurate.

So why do I play? I can’t stand sitting around, and my earlier athletic career wore down my knees and feet. Golf is pretty much my only option now. I was a professional volleyball player in Italy, and when your job involves repeatedly jumping from significant heights, a certain amount of bodily ricketiness is inevitable.

That said, golf courses are beautiful—like parkland interrupted by sand traps and tiny holes with flags. And there’s a warm camaraderie among golfers, especially my older partners who’ve long since shed most of their ego.

Your books balance humor with tension. How do you manage that?

Humor is simply built into me. It’s how I experience life, almost regardless of circumstances. Some of the most remarkable people I’ve known—including spiritual teachers and therapy mentors—had a lightness about them. They joked, teased, and made wry observations. They modeled a way of being present without layering everything with heavy meaning.

The message I took from that was simple: as long as we’re in these bodies doing what needs to be done, we might as well stay amused.

I’d like to think that if I were being attacked by thugs—and capable of kicking their collective asses—I could manage something witty while doing it. That’s probably not true, but it’s not a stretch for my characters. I create them, get inside their heads, and let them decide what they want to say. Some are wise-asses, some are unintentionally funny, and some are utterly humorless.

Maintaining tension and suspense, on the other hand, I had to learn the hard way—by writing a series of truly awful manuscripts. A fast pace helps, as do subtle cliffhangers or zingers at the ends of chapters. I always approach these decisions as a reader: what works for me, and what doesn’t?

Kinney undergoes a major internal shift. Was that inspired by personal experience?

Yes. I had a near-death experience that changed me in two fundamental ways.

I was in Mexico City during an 8.1 earthquake that lasted four and a half minutes. It threw me out of bed. The fourth floor of an old wooden hotel rolled, tilted, and swayed violently as I clung to a doorway.

It was immediately clear that any reaction was beside the point. What was going to happen was completely out of my control. I felt blank—no fear, no adrenaline. Even the rumbling ground, collapsing buildings, and people screaming didn’t faze me.

When the building tilted far enough that I could see sharp metal fenceposts below, I was fairly certain I was going to die. And strangely, that felt okay. I’d dropped into a state of radical acceptance: que sera, sera. “What next?” I thought.

Obviously, I survived. But afterward, two things were gone: my fear of dying and my illusion of control. If you can’t even rely on the ground beneath you, anything can happen at any time.

In Kinney’s Quarry, Kinney’s experience is different, but the impact is similar. For a government assassin to decide he’s no longer willing to kill—well, that creates a problem. Can his lethal skills lie dormant? Will circumstances force him back in? Can he dismantle a deadly conspiracy without killing anyone? And how does someone like Kinney live with that psychologically?

The partnership between Kinney and Reed feels unusually deep. Why was that important to you?

Kinney and Reed’s contrasting personalities create space for meaningful banter—dialogue that shows character rather than explaining it. More importantly, their ability to function as a team despite their differences is essential. Like most of us, neither can do everything alone.

I think male friendship is often underrepresented or distorted in the media. We see buddy cops and spies shooting bad guys together, but those relationships often feel superficial. I wanted something deeper.

Twice in my life, I’ve had male friendships similar to Kinney and Reed’s. Both were crucial—personally and practically. The challenges we faced weren’t as extreme as those in the novel, but they were significant and impossible to manage alone.

The unpredictability of their partnership was also essential for plot twists and suspense. Kinney, in particular, enjoys confusing opponents with out-of-the-box silliness as a form of distraction—an art he’s mastered.

Verlin Darrow is currently a psychotherapist who lives with his psychotherapist wife in the woods near the Monterey Bay in northern California. They diagnose each other as necessary. Verlin is a former professional volleyball player (in Italy), unsuccessful country-western singer/songwriter, import store owner, and assistant guru in a small, benign spiritual organization. Before bowing to the need for higher education, a much younger Verlin ran a punch press in a sheetmetal factory, drove a taxi, worked as a night janitor, shoveled asphalt on a road crew, and installed wood flooring. He missed being blown up by Mt. St. Helens by ten minutes, survived the 1985 Mexico City earthquake (8 on the Richter scale), and (so far) has successfully weathered his own internal disasters.

Find out more at https://www.verlindarrow.com.

I highly recommend Kinney's Quarry and Verlin Darrow's other books.

They are unusual, funny, well-written and have wisdom woven into them.

I have read all of them. Check them out!